Lorrain, Claude (French / 1600-1682)

Claude Gellée--known as Claude Lorrain from his birthplace, the duchy of Lorraine--was born in 1604/1605 to a humble family in the village of Chamagne, not far from Nancy. He was probably in his early teens when he left Lorraine for Rome, and according to his friend and first biographer Joachim von Sandrart, he had been trained as a pastry cook. Sandrart's details do not always agree with those provided by Claude's second biographer Filippo Baldinucci (1625-1697), but it appears that the young man soon moved to Naples, where he was a pupil of Goffredo Wals (1590/1595-1638/1640). When Claude returned to Rome two years later, he became associated with Agostino Tassi (c. 1580-1644), a specialist in landscape and illusionistic architecture, possibly as a servant and then as a pupil. In 1625 Claude traveled to Nancy to work for a year under Claude Deruet (1588-1660), the leading painter of the court of Lorraine. By 1627 he was back in Rome, where he remained for the rest of his life.

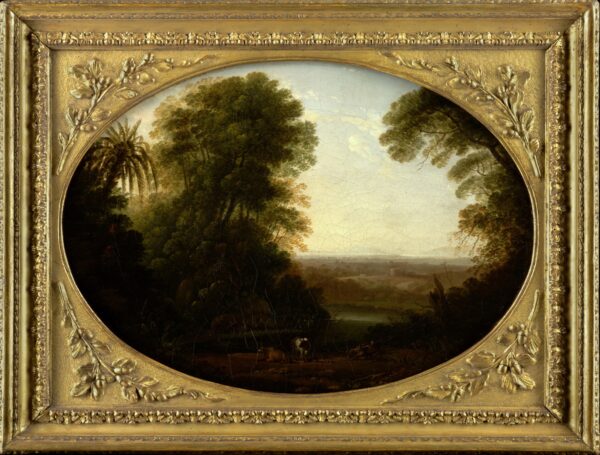

For Claude, whose dedication to landscape would never waver, Rome was a hospitable place that nurtured the careers of such specialists, most of them from north of the Alps. Claude's first dated picture, Pastoral Landscape of 1629 (Philadelphia Museum of Art), reflects his study of his teachers Wals and Tassi and of the northern landscape specialists active in Rome, Paul Bril (1554-1626) and Adam Elsheimer (1578-1610). Influenced by this generation of artists, Claude's early compositions consist of receding tracts of land accentuated by tonal modulations from dark foreground to bright green middle ground and icy blue distance. Repoussoirs, especially tall trees, unify the surface design and support the illusion of recession. Claude's work was distinguished by his ability to render the specific character of light at different times and conditions and to use light to bring pictorial unity to a scene. He honed his skill by tirelessly observing and drawing the light and atmosphere of the countryside around Rome, creating lyrical, freely executed studies that exercised his eye and hand. By contrast, his paintings were painstakingly worked out in the studio with carefully plotted perspective, calculated balance, and a close attention to detail. Baldinucci claimed that Claude employed a specialist to paint his figures, but this contention has been much debated. If true, it may have been the case only very early in his career. In fact, his figures are perfectly integrated into the landscapes by their character and color.

Success was at hand for Claude by the early 1630s. He joined the official society of painters in Rome, the Accademia di San Luca, in 1633. His work, stylistically distinctive and sought after, was imitated and even forged, prompting him by 1635 to begin an album of drawings, the Liber Veritatis (London, British Museum), which records virtually every subsequent painting he made with a notation of its date and destination. It also documents an avid international market for Claude's work. In Italy he worked for Cardinals Crescenzi, Bentivoglio, Carlo de Medici, and Angelo Giori; Pope Urban VIII; and Giulio Rospigliosi before he became pope. King Philip IV of Spain commissioned works (Madrid, Museo nacional del Prado) for the Palace of Buen Retiro. A succession of French ambassadors, including Philippe de Béthune and the marquis de Coeuvres, ordered pictures, as did the bishop of Le Mans. Claude's fame increased as many of his paintings were sent back to Paris. His forty-four etchings, in which he explored the free handling and atmospheric possibilities of this medium, were mainly done before 1641 and were an effective vehicle to build his international reputation.

Claude absorbed the lessons of Bolognese landscape painting, especially the classicism of Domenichino (1581-1641), resulting by the 1640s in a more controlled and ennobled structure. His style evolved toward the perfected and ordered conception of nature that came to be called "ideal landscape." His repertoire of subjects--mythological, pastoral, or biblical--remained constant, and the conception of small-scale figures harmoniously integrated into their setting changed little. He frequently employed monumental architecture to frame an impressive vista, as in a typical seaport scene such as Ulysses Returning Chryseis to Her Father of 1644 (Paris, Musée du Louvre). Here, figures busy themselves along the quay, and pastel banners flutter in a light breeze, but the effect is essentially calm. Claude dares to paint the sun in full view, and warm yellow sunlight drenches the harbor, backlighting the magnificent ship and glinting off the ripples on the water. His descriptive virtuosity, evident in his evocation of the humid, hazy atmosphere, is now a means to conjure a poetic mood, the nostalgia for a classical past.

In the 1650s, entering his most heroic phase, his affective powers deepened as he attained greater breadth and equilibrium in his compositions. His horizons could appear infinitely distant, the culmination of a vast panorama. In a work like Pastoral Capriccio with the Arch of Constantine of 1651 (London, Duke of Westminster), he achieves a monumentality of design in which the architectural and natural elements are in themselves strong, even grand, but locked in a secure balance in surface design and in depth. The schemata that organized Claude's early work have been superseded by subtle transitions of space and nuanced reduction of local color and detail to create a slow, undulating passage through landscape. Small, sturdy figures and animals go about their activities in serene harmony with nature. Where there is no explicit subject, the painting evokes a state of mind, a golden age.

In the last two decades of his long career, Claude worked increasingly on a larger scale, painted fewer pictures each year, and worked for more exclusive patrons. His affective powers deepened as the range of poetic moods he could conjure increased, as in The Origin of Coral of 1674 (Norfolk, England, Holkham). Even when the composition is not so extreme, naturalism seems beside the point, and a dreamlike, febrile quality imbues the last landscapes. Claude's late figures are famously elongated, especially in the torso, and a little ungainly. These attenuated figures are oddly fantastic and immaterial, as if the countryside were populated from the historical imagination with heroic characters from antique poetry. Claude's development might have been stimulated in part by the study of ancient Roman frescoes and by the very different, but equally idiosyncratic, late mythological landscapes by his friend and neighbor, Nicolas Poussin (1594-1665).

[Gail Feigenbaum, in French Paintings of the Fifteenth through the Eighteenth Century, The Collections of the National Gallery of Art Systematic Catalogue, Washington, D.C., 2009: 95-96.]