Description

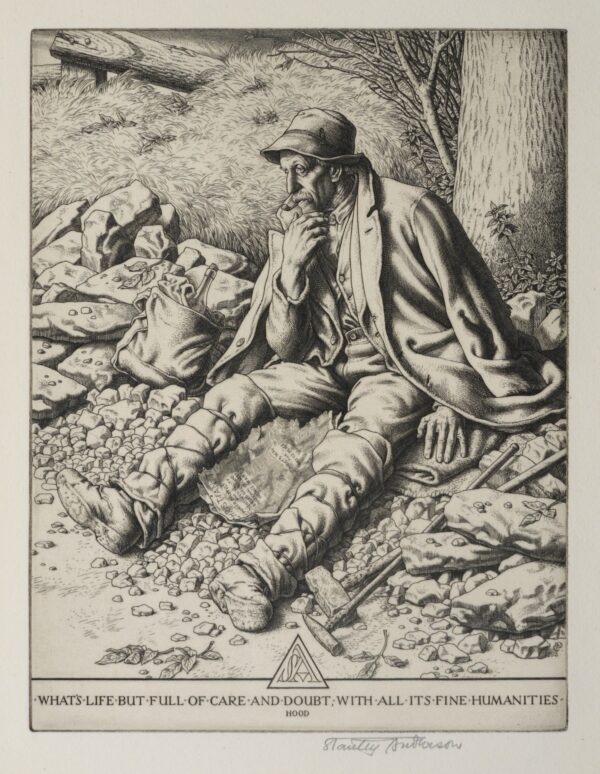

At the end of the 1920’s Stanley Anderson moved away from the use of drypoint as his primary printmaking technique, favouring instead the linear clarity of pure line engraving. During the following two decades he used this technique to produce an outstanding body of remarkable images depicting the traditional crafts and activities of rural England. The Stone-Breaker is at the heart of this body of work; dating from 1940, this outstanding study of a rural labourer was chosen by the Print Collectors’ Club as a presentation plate to represent one of the year’s finest examples of original printmaking in England.

Melancholy is tempered with anger, with a sense that steadfast manuel work – including the artist’s own efforts – may be co-opted and corrupted in an age of destruction. Driving this home is the engraved inscription Anderson borrowed from the nineteenth-century humorist Thomas Hood, whose poem ‘The Broken Dish’ imagines the subjects of a willow-pattern plate as the hapless victims of a catastrophic event beyond their control. The quote from Hood which Stanley Anderson gives beneath the image reads “What’s life but full of care and doubt, with all its fine humanities”. The newspaper which lies on the ground in front of the weary workmen reads “Christian Times. Power politics and sentimentality breed greed and national idolatry, hence war. Christ’s way, the way to peace”.

‘The Broken Dish’ A poem by Thomas Hood

What’s life but full of care and doubt

With all its fine humanities,

With parasols we walk about,

Long pigtails, and such vanities.

We plant pomegranate trees and things,

And go in gardens sporting,

With toys and fans of peacocks’ wings,

To painted ladies courting.

We gather flowers of every hue,

And fish in boats for fishes,

Build summer-houses painted blue, –

But life’s as frail as dishes!

Walking about their groves of trees,

Blue bridges and blue rivers,

How little thought them two Chinese,

They’d both be smashed to shivers!