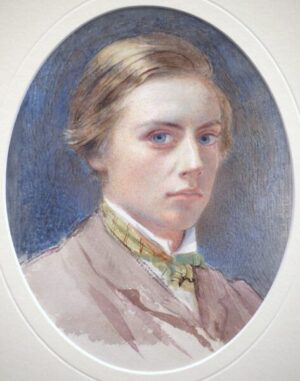

Smetham, James (1821-1889)

James Smetham produced over four hundred paintings during his lifetime. Like his good friend Dante Gabriel Rossetti, who was a major influence on his art, Smetham was a poet as well as a painter. He also wrote criticisms and recorded fascinating details on many celebrated personages of his day. His paintings ranged from portraits to Biblical interpretations, arcadian vignettes and landscapes. Smetham had great hopes and complicated theories about how audiences would understand and buy his art, but he was sadly disappointed with critical response. However, he received praise from some eminent contemporaries like John Ruskin, George Frederick Watts and Dante Gabriel Rossetti who hailed his friends' paintings as "the flower of modern art".

Smetham was born in Pateley Bridge, Yorkshire on September 8, 1821, the son of a middle-class Methodist preacher and attended school in Leeds. In childhood Smetham said he "formed the desire of becoming a painter" and afterwards "never had a thought of being anything else". He was originally apprenticed to an architect before deciding on an artistic career. In 1843 he entered the Royal Academy Schools as a probationer, but this lasted only a few months. Partly due to health reasons. Smetham did not return to London until 1851 when he began exhibiting at the Royal Academy, the British Institution, and elsewhere. That same year Smetham was hired as a drawing teacher for students training to be teachers at the Wesleyan Normal College at Westminster, and he retained this job until his final collapse in 1877; in 1854 he married Sarah Goble, a fellow teacher at the school. They would eventually have six children. Torn by his devout Methodist beliefs and bouts of mental illness, Smetham led a life that was ordered according to a strict daily regime of activities, including painting, reading the Bible, 'squaring' it's contents in tiny pictographs, walks, and church related duties. He chose to isolate himself in rural Stoke Newington and rejecting what he called "studio life in its widest sense - haunting the clubs, sketching clubs, lecture rooms - the company of dealers and patrons, things utterly revolting and impossible to me" yet ironically "necessary to that growing murmur of influence that is preliminary of fame".

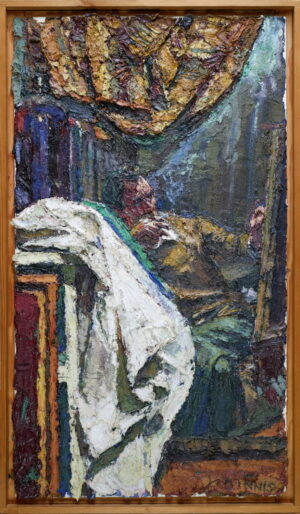

Smetham worked in a range of genres, including religious and literary themes as well as portraiture; but he is perhaps best known as a landscape painter. His "landscapes have a visionary quality" reminiscent of the work of William Blake, John Linnell, and Samuel Palmer. Out of a lifetime output of some 430 paintings and 50 etchings, woodcuts, and book illustrations, his 1856 painting The Dream is perhaps his best-known work but his signal work is The Hymn of the Last Supper a very ambitious subject for him to undertake but one which worked out magnificently. His choice of subject was sometimes somewhat bizarre; one of his best paintings is The Death of Earl Siward which depicts the dying earl, dressed in full armour, standing up and being supported by his servants as 'He did not wish to die lying down like a cow'.

He was also an essayist and art critic; an article on Blake (in the form of a review of Alexander Gilchrist's Life of William Blake), which appeared in the January 1869 issue of the Quarterly Review, influenced and advanced recognition of Blake's artistic importance. Other Smetham articles for the Review were "Religious Art in England" (1861), "The Life and Times of Sir Joshua Reynolds" (1866), and "Alexander Smith" (1868). He also wrote some poetry. In one of his notebooks he attempted to illustrate every verse in the Bible. (Smetham habitually created miniature, postage-stamp-sized pen-and-ink drawings, in a process he called "squaring." He produced thousands of these in his lifetime.) In the fall of 1877 he succumbed to a final debilitating attack after which he withdrew from the world, became delusional and virtually ceased talking. His loyal friends, including Rossetti organized an exhibition and sale of his work. After more than a decade of emotional and psychological anguish, Smetham died on Febuary 5, 1889. The inscription on his tomb in Highgate Cemetery is as follows, "I shall be satisfied when I awake with thy likeness."

Smetham's letters, posthumously published by his widow, throw light upon Rossetti, John Ruskin, and other contemporaries, and have been praised for their literary and spiritual qualities. His surviving journals and notebooks show that Smetham practiced an almost stream of consciousness type of writing that he called "ventilating," as a method of religious self-analysis. These writings delineate the depression that came to dominate Smetham's outlook.

Lit: Susan P. Casteras, James Smetham: Artist, Author, Pre-Raphaelite Associate, Aldershot, U.K., Scholar Press, 1995: James Smetham, The Letters of James Smetham: With an Introductory Memoir, Sarah Smetham and William Davies, eds., London, Macmillan, 1892.