Blake, William (1757-1827)

William Blake was born at 28 Broad Street, Golden Square, Soho, where his father had a hosiery business. In 1767 he began study at Henry Pars’ Drawing Class in the Strand, and in 1771 was apprenticed to James Basire of Great Queen Street, Lincoln’s Inn Fields, who was engraver to the Society of Antiquaries of London. In 1779 he was admitted to the Royal Academy Schools as a student. He married Catherine Boucher, the illiterate daughter of a market gardener, in 1782, and moved to Green Street, near Leicester Square. He returned to Broad Street, this time at number 27, when his father died in 1784 (27), to set up in business as a print seller with James Parker, a friend and former fellow apprentice. The partnership ended in 1787, and Blake moved to nearby Poland Street.

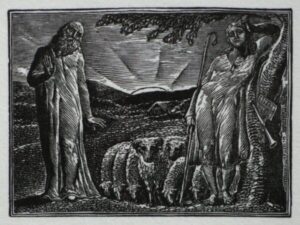

In the same year Blake’s brother Robert died. Blake claimed that the spirit of Robert came to him in a vision in the night, and revealed the technique of combining text and pictures on one engraved plate. He hand produced the Songs of Innocence using this new method in 1789 with the help of his wife, having taught her to read and write. The text and illustrations were printed from copper plates, and the illustrations then finished by hand with watercolours. They moved to No 13 Hercules Buildings in Lambeth in 1791, and it was in this period that he produced many of his ‘prophetic’ books : The Visions of the Daughters of Albion, America a Prophecy, The Songs of Experience and The First Book of Urizen.

In September 1800 he left London for Felpham, Sussex (about 50 miles south west of London on the south coast), to live near William Hayley, an eccentric gentleman poet who had written biographies of Milton and Cowper, and through whom he hoped to get commissions for engraving. But by the beginning of 1803 he had tired of the trivial nature of these commissions. He had come to believe that only in London could he carry on his visionary studies, and he moved back to the capital, to 17 South Moulton Street, near Tyburn (now Marble Arch). He began work on his illuminated books Milton and Jerusalem, but struggled to find other commercial work. In May 1809 he held an exhibition on the first floor of his brother’s hosiery shop in Broad Street, but few people attended, and he was dismissed by Robert Hunt in a review in The Examiner as ‘an unfortunate lunatic whose personal inoffensiveness secures him from confinement’.

After 1818 his work found admirers amongst water-colourists of the next generation, particularly John Linnell and John Varley who encouraged him and commissioned works. Linnell wrote : ‘I soon encountered Blake’s peculiarities and [was] somewhat taken aback by the boldness of some of his assertions. I never saw anything the least like madness, for I never opposed him spitefully, as many did – but being really anxious to fathom, if possible, the amount of truth which might be in his most startling assertions, I generally met with a sufficiently rational explanation in the most really friendly and conciliatory tone. Even when John Varley, to whom I introduced to Blake, and who readily devoured all the marvellous in Blake’s most extravagant utterances – even to Varley, Blake would occasionally explain unasked how he believed that both Varley and I could see the same visions as he saw – making it evident to me, that Blake claimed the possession of some powers, only in a greater degree, that all men possessed, and which they undervalued in themselves but lost through love of sordid pursuits – pride, vanity, and the unrighteous mammon.’ He died in 1827, and was buried in an unmarked grave in the dissenter’s graveyard in Bunhill Fields.

Showing the single result