Description

At Fontainebleau, Napoleon revived the court’s autumn hunting trips, which for reasons of economy Louis XVI had suspended in 1787. He went hunting there for about 50 days in the autumns of 1807, 1809 and 1810. About 10,000 people were lodged in the palace and the town. As they had under Louis XVI, theatre companies came from Paris to entertain courtiers in the palace theatre in the evening.

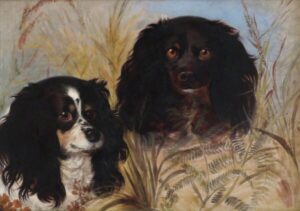

By 1812 the imperial hunt had a staff of 100 men, 115 horses and 170 hounds, and cost about 445,000 francs a year, compared to over a million under Louis XVI. Many of its officials had served in the hunts of Louis XVI. They included Beauterne, porte-arquebuse of the King and the Emperor; Bongars, page de la venerie; Caqueray; and Hanneucourt. Their hunting skills were more important than their political antecedents. After his marriage to the Archduchess Marie Louise in 1810, with the increasing grandeur of the court, Napoleon devoted more hours to such a traditional monarchical occupation as the hunt, as well as to attendance at the theatre and at mass.

Hunting was so important that it could decide where the court resided. The proximity of hunting forests was one reason for the choice, as a royal residence, of Windsor, Versailles, Stupinigi, Hubertusberg, and many other sites. Conversely, the choice of these sites as royal residences ensured that the surrounding forests were well maintained. The landscape of the Ile de France is still dominated by the royal hunting forests of Versailles, Marly, Saint-Germain, Compiegne, Vincennes, Fontainebleau, and Rambouillet.

In addition to the pleasure and food it provided, hunting could also acquire a political and hierarchical function. Hunting was a visible assertion of domination over the land and the animal kingdom. It also protected the ruler’s subjects and their herds from boar, wolves and other vermin. The stag was the noblest beast, hunting it the noblest sport. Furthermore, hunting was believed to be a school of war, masculinity and horsemanship. It taught courage, comprehension of landscape, and the art of the cavalry charge. In l’Ecole de Cavalerie of 1751, Robichon de La Guerroniere described hunting: it is the pastime which Kings and Princes prefer to all others. This inclination is no doubt based on the conformity existing between hunting and war. In both, in effect, there is an object to tame, hardships to endure, dangers to avoid and tricks to practice.

Even in the twentieth century hunting continued to be regarded, by some generals, as ‘the continuation of a cavalry charge by other means. Indeed, hunting horses were often used by cavalry regiments.

There was a further reason for the popularity of royal hunts, in addition to the thrill of the chase, the assertion of sovereignty, and their appeal as a school of war. The fourth reason was a court’s need for mass entertainment. Royal hunts, as many cycles of pictures commissioned by monarchs prove occupied large numbers of people and vast stretches of land, acquainting subjects with their rulers, and vice versa. They required guards; hunt servants; musicians (royal hunts were always accompanied by music); dog-keepers; beaters; the monarch and his companions; and spectators. Hunts were a form of mass sociability which became the rural equivalent of a court ball or royal opera: a means of serving the king’s pleasure and advertising his power.

Extracts taken from Philip Mansel’s, The Survival of the Royal Hunt in France: from Louis XVI to Napolean III.