Description

As the son of a bandmaster, Louis Antoine Jullien (originally spelled “Julien,” plus the names of 36 godfathers who were members of the Sisteron Philharmonic) gained knowledge early on of instruments and music. Yet he was 21 before he joined the composition class of Le Carpentier at the Paris Conservatoire in 1833, and later one of Jules Halévy (the composer of La Juive and, some said, Rosita, the rage-of-Paris waltz Jullien claimed as his own). The rebellious pupil refused to do any exercises, insisting instead on playing new dance pieces in his composition classes. Although he quit in 1836 without a single citation, Jullien soon after was conducting dance music at Le Jardin Truc. Quadrilles became his specialty — the first one based on themes from Meyerbeer’s Les Huguenots. Eventually, “a Repertoire of 1200 Pieces” included English, Scottish, Irish, French, American, Russian, Hungarian, Polish, Indian, and even Chinese quadrilles.

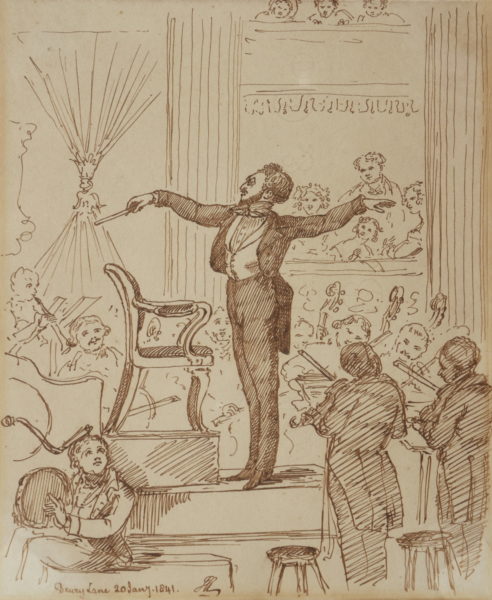

“Insolvency,” a recurring plague in 22 remaining years, drove him to London in 1838. There he began a series in 1840 called Concerts d’été with an orchestra of 90 and a chorus of 24, followed by Concerts d’hiver in 1841 with a chorus of 80, and Concerts de société in 1842, which were moved to the English Opera House from Drury Lane Theater. At one of these he led the first British performance of Rossini’s Stabat Mater. By this time Jullien was presenting concerts annually that ended in 1859, always at the close of the year. He played his Monster Quadrille in the beginning, but thereafter a different one each season. Some featured a military band in addition to his ever-larger orchestra. By 1843 he was conducting complete Beethoven symphonies, always with a jeweled baton and white gloves presented on a silver salver. He added a velvet-covered throne to his podium, onto which he sank purportedly exhausted after each performance.

Jullien affected an open coat, fancily embroidered white shirts, lace wristbands folded back over his coat sleeves, a large mane of black hair, and a mustache — all of which added glamour to the excited delight of audiences. He toured Great Britain tirelessly every season, even opening a shop for the sale of his music in Regent Street. However, in 1847 he leased Drury Lane for operas to be performed in English, hiring Berlioz as conductor and Sir Henry Bishop (“Home, Sweet Home”) as rehearsal “inspector-superintendent.” This came a-cropper, and Jullien was bankrupt a year later. In 1849 he announced a “monster musical concert and congress” with 400 players, three choruses, and three military bands, but it too was a financial disaster. He wrote an opera in 1852, produced it lavishly at his own expense, but was ruined by a run of only five performances. Time then for America, where he arrived in June 1853 for a month of concerts in NY’s Castle Garden, complete with a new American Quadrille (and Theodore Thomas in his orchestra). After touring, which included new American compositions, he ended a year’s stay with a NY Crystal Palace concert produced by his contemporary (and soulmate), P.T. Barnum. It culminated in Night, or the Fireman’s Quadrille, including the arrival of three companies to extinguish a real fire with real water. Jullien returned to London enriched, but lost his entire collection of manuscripts in the Covent Garden fire of 1856. He conducted a season of oratorios, then a provincial tour with reduced forces before returning to France in 1859. Imprisoned for debt, he was released later on, but in 1860 died impoverished in an insane asylum.