Description

English scene painters, the Grieve dynasty, were pre-eminent among nineteenth-century stage designers. They spanned three generations: the scion, John Henderson (1770–1845); his sons Thomas (1799–1882) and William (1800–44), and Thomas Walford (1841–82). Examples of their work can be seen on the website of the V&A.

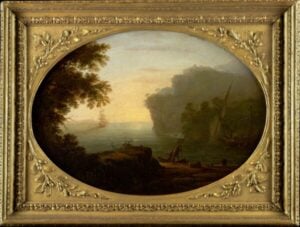

The La Pérouse expedition was an ill-fated voyage of exploration that left France in 1785 with two frigates under the command of Jean-François de Galaup de La Pérouse, and disappeared three years later in the South Pacific. Part of the early mystique of the La Pérouse story was that for almost forty years no one knew what had become of the expedition.

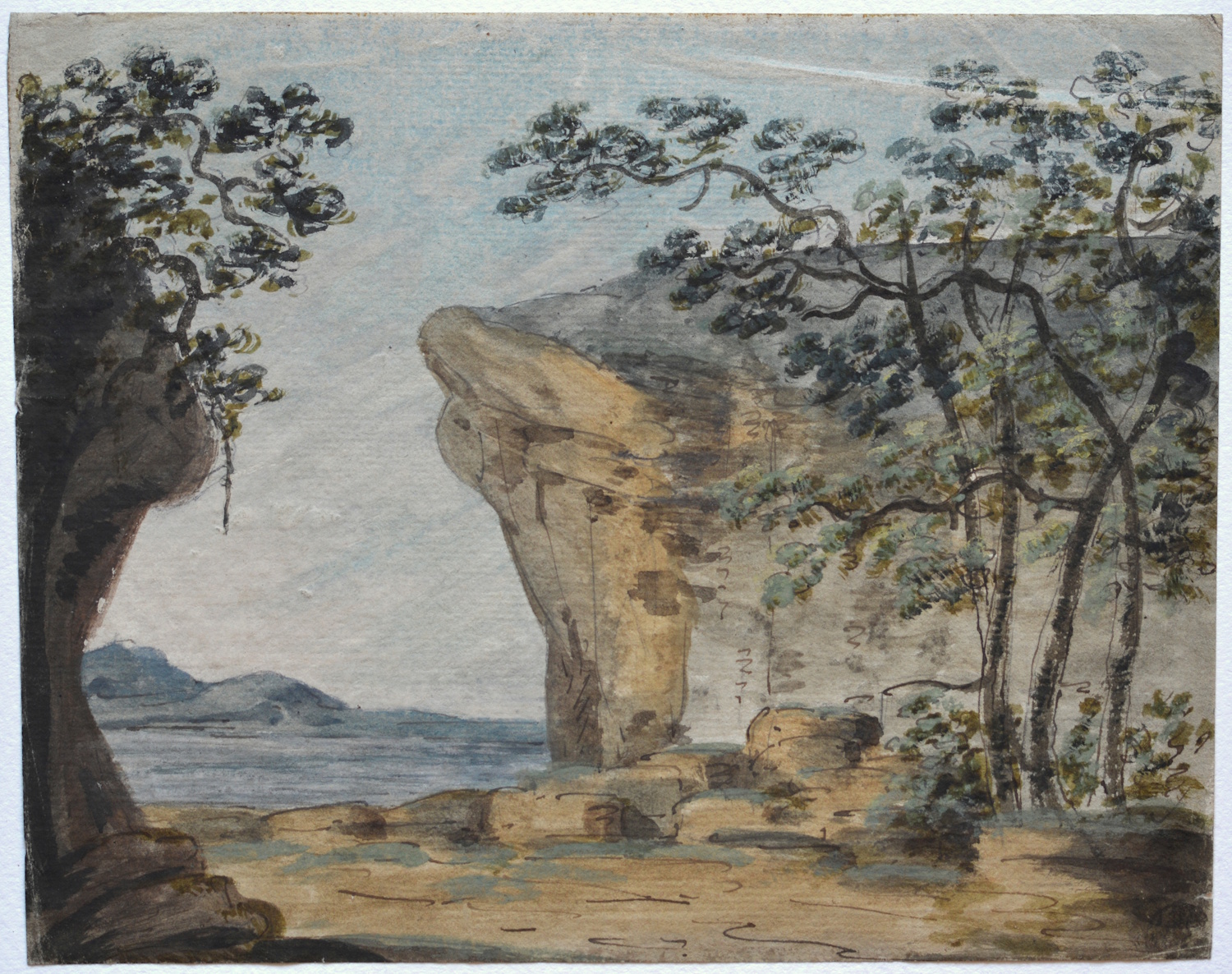

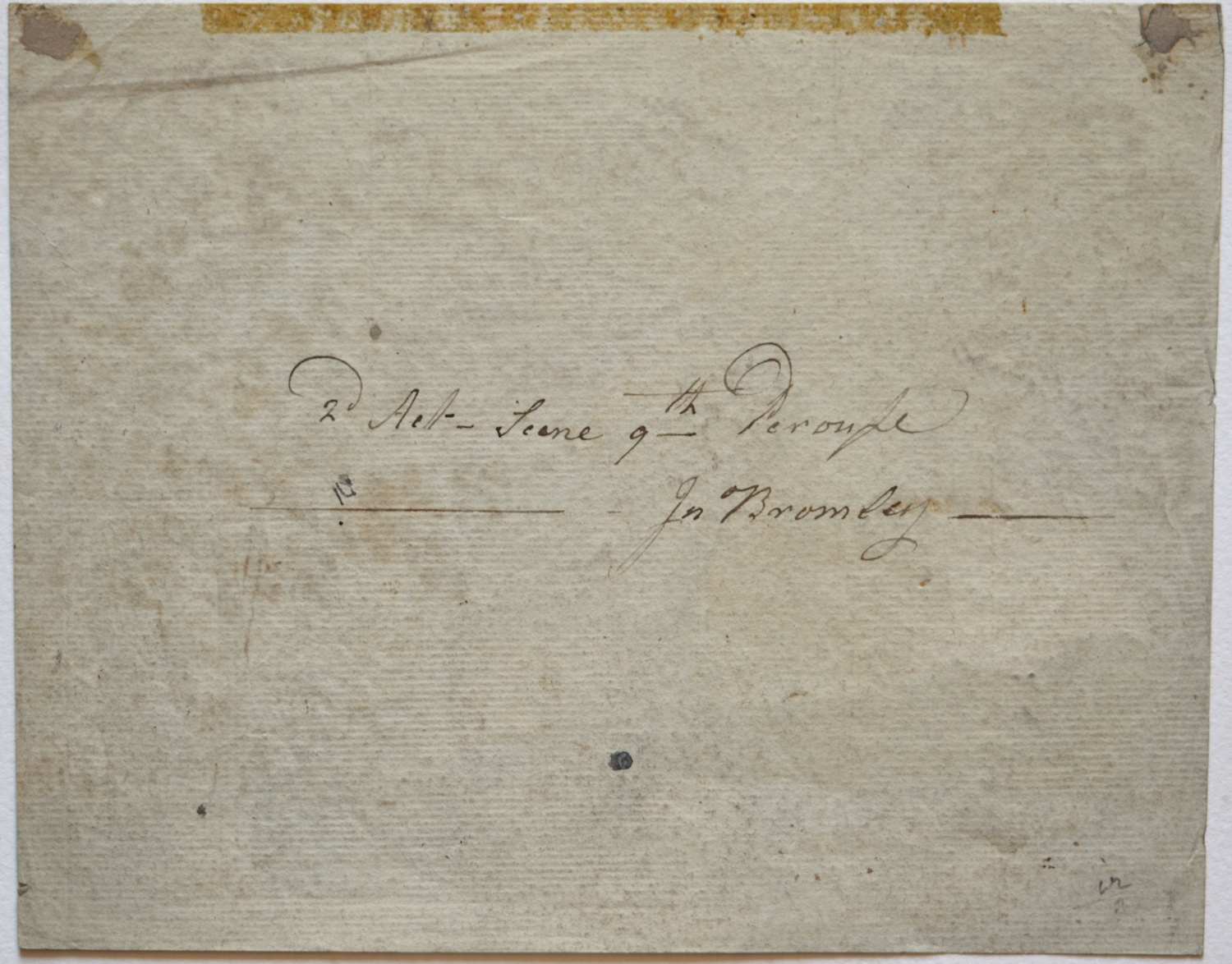

La Pérouse and his men had not been missing ten years before fictional speculations about their fate began to appear on stage and in print. One of the earliest and most successful of these was La Peyrouse, a Drama in Two Acts, written in 1797 by the popular and prolific German playwright August von Kotzebue. In the play, La Pérouse is the lone survivor of the wreck. He’s on a small island in the South Pacific with Malvina, a native woman who has forsaken her violent family to be with La Pérouse and their son, Charles. The play takes place on the day when a French ship shows up and finds La Pérouse. Awkwardly, the ship’s passengers include La Pérouse’s wife, Adelaide (not her name in real life), and their youngest child, Henry (in real life, the La Pérouses had no children). Melodramatic hijinks ensue, with each woman trying to claim her man, each character threatening suicide, and each woman then trying to renounce her claim. Then Adelaide’s brother Clairville turns up. (In real life La Pérouse’s brother-in-law was named Frédéric Broudou; a member of the expedition, he presumably perished with La Pérouse.) The fictional Clairville suggests they all remain on the island, with the two women living as “sisters” in one hut and La Pérouse living in another as their “brother.” Clairville, meanwhile, goes to England to fetch the rest of La Pérouse’s family, who have fled France and are only too delighted to settle on this tropical island (in real life they weathered the tumult of the Revolution unscathed).

In 1801, a year after Kotzebue’s play appeared in London, an English rebuttal, Perouse; or, The Desolate Island by John Fawcett, came out. The first page of the published edition of this play acknowledges the debt to Kotzebue, but complains that his ending is “by no means likely to satisfy an audience of this or probably any country,” and proposes that this version of the story will be more “suited to an English taste.”

In Fawcett’s Perouse, La Pérouse is still the only survivor of the shipwreck, and still ends up in the company of a native woman on an island (located somewhere “north of Japan”). As in Kotzebue’s play, a ship arrives to rescue La Pérouse, and again, just as in Kotzebue, Madame de la Pérouse and her son are on board. But instead of being compassionate and generous, Umba, the native woman with whom La Pérouse has been living, is jealous and violent. She betrays him to her hostile countrymen, who swoop in and capture La Pérouse, his wife, and their son. They are all about to be killed, but are saved—first, through the intervention of a loyal and savvy chimpanzee (played on stage by a man), and finally, by the timely arrival of a group of marines, who kill all of the natives. There are huzzas all around, and La Pérouse and his family return to France. Judging from its continued appearance in English theatre notices well into the 1820s, Perouse was a great success.